The Supreme Court in Operation

The Constitution implies, but does not specifically state, that the Supreme Court has the power to declare laws unconstitutional, both those enacted by Congress and by the states. The principle, which is known as judicial review, was firmly established in the case of Marbury v. Madison (1803). The decision, issued by Chief Justice John Marshall, was the first time the court invalidated an act of Congress (part of the Judiciary Act of 1789). Under Marshall, other key cases were decided that strengthened the position of the Supreme Court. In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), for example, the sanctity of contracts was upheld and a state law was ruled unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court under Marshall practiced judicial nationalism; its decisions favored the federal government at the expense of the states. In McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), it broadly defined the elastic clause by ruling that a state could not tax a federal bank, and in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), it declared that a state could not regulate interstate commerce.

The Court has not always supported a larger role for the federal government. It initially found much of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal legislation unconstitutional, primarily for violating the economic rights of individuals and companies. Roosevelt responded by trying to increase the size of the Court, which would let him appoint new justices sympathetic to his program. This attempt to "pack" the Court failed, but around that time the Court began ruling in Roosevelt's favor anyway.

The appointment of Supreme Court justices

Because Supreme Court justices serve for life and their decisions have a major impact on American society, their appointments are probably the most important that a president makes. The selection is certainly not above politics. Historically, 90 percent of the justices come from the same political party as the president who appointed them. As with the cabinet, concern about making the Court more inclusive is also a factor. The overriding concern, however, is usually a nominee's judicial philosophy: How does a candidate view the role of the Court, and what is his or her stand on the issues that might come before the Court?

Unlike the hearings for judges in the lower federal courts, the confirmation of Supreme Court justices is highly publicized and sometimes controversial. Robert Bork, a conservative nominated by President Ronald Reagan, was rejected by the Democrat-controlled Senate. Clarence Thomas narrowly won confirmation following highly emotional hearings during which charges of sexual harassment were made against him. The attention given the confirmation process reflects the impact that the Court's decisions have on Americans' lives and the issues about which they have strong feelings, such as abortion, school prayer, and the rights of criminal defendants.

A case comes to the Supreme Court

Cases are appealed to the Supreme Court through a writ of certiorari, which is a request for review based on the particular issues in the case. The Court may receive as many as 7,000 such appeals during a term. These are screened and summarized by the justices' law clerks, and the summaries are discussed in conferences held twice a week. Under the so-called rule of four, only four of the nine justices have to agree to hear a case before it is placed on the docket. The docket is the Supreme Court's agenda and, in effect, the list of cases accepted for review. Typically, the Court considers only about 100 cases a year; for the remainder, the decision of the lower court stands.

A case before the Court

Attorneys for both sides file briefs, which are written arguments that contain the facts and legal issues involved in the appeal. The term is misleading because a "brief" may run hundreds of pages and include sociological, historical, and scientific evidence, as well as legal arguments. Groups or individuals who are not directly involved in the litigation but have an interest in the outcome may submit, with permission of the Court, an amicus curiae (literally "friend of the court") brief stating their position. After the briefs are filed, attorneys may present their case directly to the Court through oral arguments. Just 30 minutes are allotted to each side, and the attorneys' arguments may be frequently interrupted by questions from the justices.

A decision is reached

After reviewing the briefs and hearing oral arguments, the justices meet in conference to discuss the case and ultimately take a vote. A majority of the justices must agree, meaning five out of the nine justices in a full Court. At this point, the opinion is drafted. This is the written version of the Court's decision. If in the majority, the chief justice can draft the opinion, but more often this task is assigned to another justice in the majority. The senior associate justice voting in the majority makes the assignment when the chief justice is in the minority.

The opinion usually goes through numerous drafts, which are circulated among the justices for comment. Additional votes are sometimes required, and a justice may change from one side to another. After final agreement is reached, a majority opinion is issued that states the Court's decision (judgment) and presents the reasons behind the decision (argument). Usually the decision builds on previous court rulings, called precedent, because a central principle guiding judicial practices is the doctrine of stare decisis (which means "let the decision stand"). A justice who accepts the decision but not the majority's reasoning may write a concurring opinion. Justices who remain opposed to the decision may submit a dissenting opinion. Some dissents have been so powerful that they are better remembered than the majority opinion. It may also happen that, as the times and the makeup of the Court change, a dissenting view becomes the majority opinion in a subsequent case. When the Court chooses to overrule precedent, however, the justices responsible may be criticized for violating the stare decisis principle.

The rationale for decisions

Sometimes Supreme Court decisions require statutory interpretation, or the interpretation of federal law. Here the Court may rely on the plain meaning of a law to determine what Congress or a state legislature intended, or it may turn to the legislative history, the written record of how the bill became a law. Similar forms of reasoning apply in cases of constitutional interpretation, but justices (especially liberals) often are willing to use a third method: the living Constitution approach. They update the meaning of provisions, sticking neither to literal interpretation nor to historical intent, so that the Constitution can operate as "a living document."

Court watchers group the justices into liberal, moderate, and conservative camps. The members of the Court certainly have personal views, and it is naive to believe that these views do not play a part in decisions. What is more important, however, is how a justice views the role of the Court. Proponents of judicial restraint see the function of the judiciary as interpreting the law, not making new law, and they tend to follow statutes and precedents closely. Those who support judicial activism, on the other hand, interpret legislation more loosely and are less bound by precedent. They see the power of the Court as a means of encouraging social and economic policies.

Implementing Supreme Court decisions

The Supreme Court has no power to enforce its decisions. It cannot call out the troops or compel Congress or the president to obey. The Court relies on the executive and legislative branches to carry out its rulings. In some cases, the Supreme Court has been unable to enforce its rulings. For example, many public schools held classroom prayers long after the Court had banned government-sponsored religious activities.

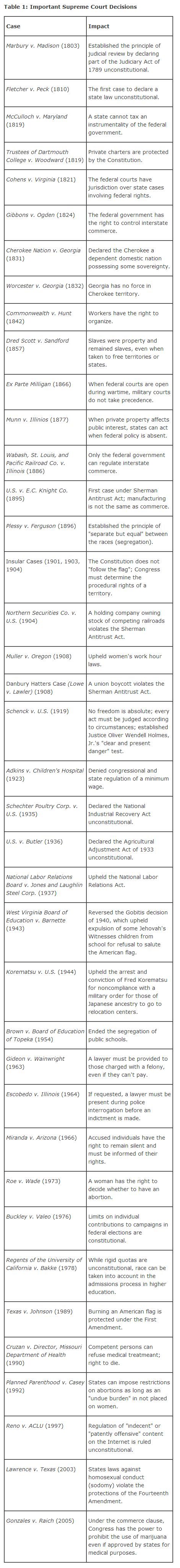

Table 1 lists some of the more important Supreme Court decisions over the years and briefly explains the impact of each decision.