Depreciation is the process of allocating the cost of long‐lived plant assets other than land to expense over the asset's estimated useful life. For financial reporting purposes, companies may choose from several different depreciation methods. Before studying some of the methods that companies use to depreciate assets, make sure you understand the following definitions.

-

Useful life is an estimate of the productive life of an asset. Although usually expressed in years, an asset's useful life may also be based on units of activity, such as items produced, hours used, or miles driven.

-

Salvage value equals the value, if any, that a company expects to receive by selling or exchanging an asset at the end of its useful life.

-

Depreciable cost equals an asset's total cost minus the asset's expected salvage value. The total amount of depreciation expense assigned to an asset never exceeds the asset's depreciable cost.

-

Net book value is an asset's total cost minus the accumulated depreciation assigned to the asset. Net book value rarely equals market value, which is the price someone would pay for the asset. In fact, the market value of an asset, such as a building, may increase while the asset is being depreciated. Net book value simply represents the portion of an asset's cost that has not been allocated to expense.

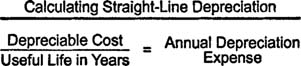

Straight‐line depreciation. There are many depreciation methods available to companies. Straight‐line depreciation is the method that companies most frequently use for financial reporting purposes. If straight‐line depreciation is used, an asset's annual depreciation expense is calculated by dividing the asset's depreciable cost by the number of years in the asset's useful life.

Another way to describe this calculation is to say that the asset's depreciable cost is multiplied by the straight‐line rate, which equals one divided by the number of years in the asset's useful life.

Calculating Straight‐Line Depreciation

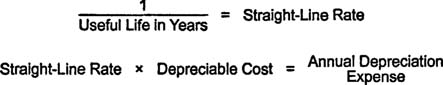

Suppose a company purchases a $90,000 truck and expects the truck to have a salvage value of $10,000 after five years. The depreciable cost of the truck is $80,000 ($90,000 – $10,000), and the asset's annual depreciation expense using straight‐line depreciation is $16,000 ($80,000 ÷ 5).

|

Cost

|

$90,000

|

|

Less: Salvage Value

|

(10,000)

|

|

Depreciable Cost

|

$80,000

|

The following table summarizes the application of straight‐line depreciation during the truck's five‐year useful life.

|

Straight-Line Depreciation

|

|

|

Depreciable Cost

|

|

|

|

|

Cost

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$90,000

|

|

Year 1

|

20%

|

×

|

$80,000

|

=

|

$16,000

|

$16,000

|

74,000

|

|

Year 2

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

32,000

|

58,000

|

|

Year 3

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

48,000

|

42,000

|

|

Year 4

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

64,000

|

26,000

|

|

Year 5

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

80,000

|

10,000

|

At the end of year five, the $80,000 shown as accumulated depreciation equals the asset's depreciable cost, and the $10,000 net book value represents its estimated salvage value.

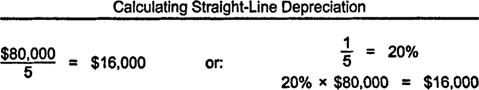

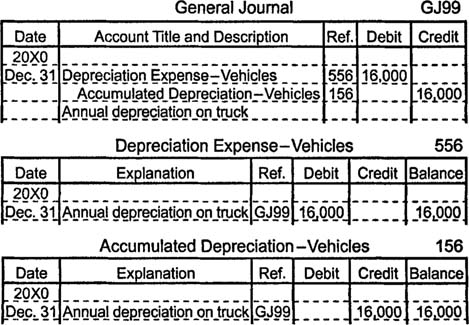

To record depreciation expense on the truck each year, the company debits depreciation expense–vehicles for $16,000 and credits accumulated depreciation–vehicles for $16,000.

If another depreciation method had been used, the accounts that appear in the entry would be the same, but the amounts would be different.

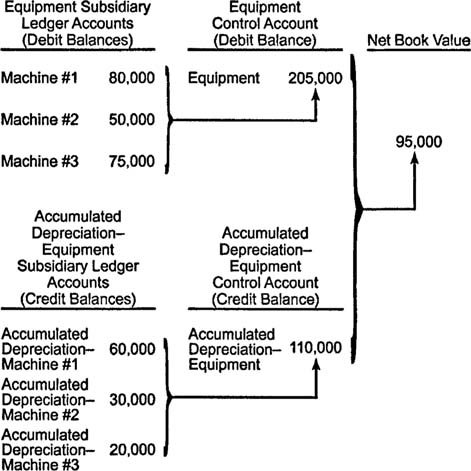

Companies use separate accumulated depreciation accounts for buildings, equipment, and other types of depreciable assets. Companies with a large number of depreciable assets may even create subsidiary ledger accounts to track the individual assets and the accumulated depreciation on each asset.

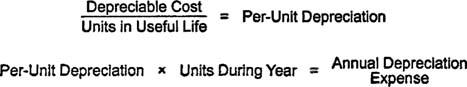

Units‐of‐activity depreciation. The useful life of some assets, particularly vehicles and equipment, is frequently determined by usage. For example, a toy manufacturer may expect a certain machine to produce one million dolls, or an airline may expect an airplane to provide ten thousand hours of flight time. Units‐of‐activity depreciation, which is sometimes called units‐of‐production depreciation, allocates the depreciable cost of an asset based on its usage. A per‐unit cost of usage is found by dividing the asset's depreciable cost by the number of units the asset is expected to produce or by total usage as measured in hours or miles. The per‐unit cost times the actual number of units in one year equals the amount of depreciation expense recorded for the asset that year.

Calculating Units‐of‐Activity Depletion

If a truck with a depreciable cost of $80,000 ($90,000 cost less $10,000 estimated salvage value) is expected to be driven 400,000 miles during its service life, the truck depreciates $0.20 each mile ($80,000 ÷ 400,000 miles = $0.20 per mile). The following table shows how depreciation expense is assigned to the truck based on the number of miles driven each year.

|

Units-of-Activity Depreciation

|

|

|

Per-Unit Depreciation

|

|

|

|

|

Cost

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$90,000

|

|

Year 1

|

110,000

|

×

|

$0.20

|

=

|

$22,000

|

$22,000

|

68,000

|

|

Year 2

|

70,000

|

×

|

0.20

|

=

|

14,000

|

36,000

|

54,000

|

|

Year 3

|

90,000

|

×

|

0.20

|

=

|

18,000

|

54,000

|

36,000

|

|

Year 4

|

80,000

|

×

|

0.20

|

=

|

16,000

|

70,000

|

20,000

|

|

Year 5

|

50,000

|

×

|

0.20

|

=

|

10,000

|

80,000

|

10,000

|

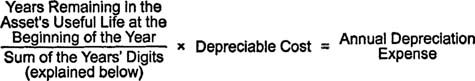

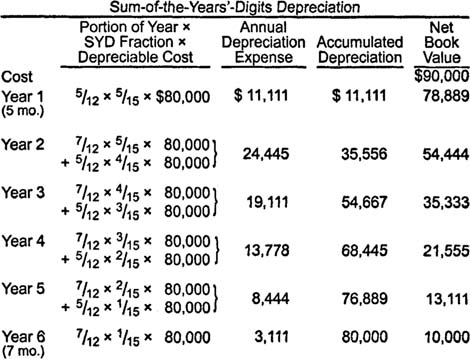

Sum‐of‐the‐years'‐digits depreciation. Equipment and vehicles often provide greater benefits when they are new than when they approach the end of their useful lives and more frequently require repairs. Using sum‐of‐the‐years'‐digits depreciation is one way for companies to assign a disproportionate share of depreciation expense to the first years of an asset's useful life. Under this method, depreciation expense is calculated using the following equation.

Calculating Sum‐of‐Year's‐Digits Depletion

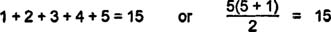

The equation's denominator (the sum of the years' digits) can be found by adding each integer from one through the number of years in the asset's useful life (1 + 2 + 3…) or by substituting the number of years in the asset's useful life for x in the following equation.

The sum of the years' digits for an asset with a five‐year useful life is 15.

Therefore, depreciation expense on the asset equals five‐fifteenths of the depreciable cost during the first year, four‐fifteenths during the second year, three‐fifteenths during the third year, two‐fifteenths during the fourth year, and one‐fifteenth during the last year.

The following table shows how the sum‐of‐the‐years'‐digits method allocates depreciation expense to the truck, which has a depreciable cost of $80,000 ($90,000 cost less $10,000 expected salvage value) and a useful life of five years.

|

Sum-of-the-Years'-Digits Depreciation

|

|

|

Depreciable Cost

|

|

|

|

|

Cost

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$90,000

|

|

Year 1

|

5/15

|

×

|

$80,000

|

=

|

$26,667

|

$26,667

|

63,333

|

|

Year 2

|

4/15

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

21,333

|

48,000

|

42,000

|

|

Year 3

|

3/15

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

64,000

|

26,000

|

|

Year 4

|

2/15

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

10,667

|

74,667

|

15,333

|

|

Year 5

|

1/15

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

5,333

|

80,000

|

10,000

|

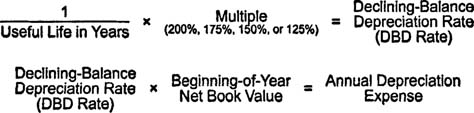

Declining‐balance depreciation. Declining‐balance depreciation provides another way for companies to shift a disproportionate amount of depreciation expense to the first years of an asset's useful life. Declining‐balance depreciation is found by multiplying an asset's net book value (not its depreciable cost) by some multiple of the straight‐line rate for the asset. The straight‐line rate is one divided by the number of years in the asset's useful life. Companies typically use twice (200%) the straight‐line rate, which is called the double‐declining‐balance rate, but rates of 125%, 150%, or 175% of the straight‐line rate are also used. Once the declining‐balance depreciation rate is determined, it stays the same for the asset's useful life.

Calculating Declining‐Balance Deprciation

To illustrate double‐declining‐balance depreciation, consider the truck that has a cost of $90,000, an expected salvage value of $10,000, and a five‐year useful life. The truck's net book value at acquisition is also $90,000 because no depreciation expense has been recorded yet. The straight‐line rate for an asset with a five‐year useful life is 20% (1 ÷ 5 = 20%), so the double‐declining‐balance rate, which uses the 200% multiple, is 40% (20% x 200% = 40%). The following table shows how the double‐declining‐balance method allocates depreciation expense to the truck.

|

Double-Declining-Balance Depreciation

|

|

|

Beginning-of-Year Book Value

|

|

|

|

|

Year 1

|

40%

|

×

|

$90,000

|

=

|

$36,000

|

$36,000

|

$54,000

|

|

Year 2

|

40%

|

×

|

54,000

|

=

|

21,600

|

57,600

|

32,400

|

|

Year 3

|

40%

|

×

|

32,400

|

=

|

12,960

|

70,560

|

19,440

|

|

Year 4

|

40%

|

×

|

19,440

|

=

|

7,776

|

78,336

|

11,664

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Limited to $1,664 so book value does not go below salvage value.

At the end of an asset's useful life, the asset's net book value should equal its salvage value. Although 40% of $11,664 is $4,666, the truck depreciates only $1,664 during year five because net book value must never drop below salvage value. If the truck's salvage value were $5,000, depreciation expense during year five would have been $6,664. If the truck's salvage value were $20,000, then depreciation expense would have been limited to $12,400 during year three, and no depreciation expense would be recorded during year four or year five.

Comparing depreciation methods. All depreciation methods are designed to systematically allocate the depreciable cost of an asset to expense during the asset's useful life. Although total depreciation expense is the same no matter what depreciation method is used, the methods differ from each other in the specific assignment of depreciation expense to each year or accounting period, as shown in the following comparison of annual depreciation expense over five years using a truck's depreciable cost of $80,000.

|

Annual Depreciation Expense

|

|

Straight-Line Depreciation

|

Units-of-Activity Depreciation

|

Sum-of-the-Years'-Digits Depreciation

|

Double-Declining-Balance Depreciation

|

|

Year 1

|

$16,000

|

$22,000

|

$26,667

|

$36,000

|

|

Year 2

|

16,000

|

14,000

|

21,333

|

21,600

|

|

Year 3

|

16,000

|

18,000

|

16,000

|

12,960

|

|

Year 4

|

16,000

|

16,000

|

10,667

|

7,776

|

|

Year 5

|

16,000

|

10,000

|

5,333

|

1,664

|

|

$80,000

|

$80,000

|

$80,000

|

$80,000

|

The sum‐of‐the‐years'‐digits and double‐declining‐balance methods are called accelerated depreciation methods because they allocate more depreciation expense to the first few years of an asset's life than to its later years.

Partial‐year depreciation calculations. Partial‐year depreciation expense calculations are necessary when depreciable assets are purchased, retired, or sold in the middle of an annual accounting period or when the company produces quarterly or monthly financial statements. The units‐of‐activity method is unaffected by partial‐year depreciation calculations because the per‐unit depreciation expense is simply multiplied by the number of units actually used during the period in question. For all other depreciation methods, however, annual depreciation expense is multiplied by a fraction that has the number of months the asset depreciates as its numerator and twelve as its denominator. Since depreciation expense calculations are estimates to begin with, rounding the time period to the nearest month is acceptable for financial reporting purposes.

Suppose the truck is purchased on July 26 and the company's annual accounting period ends on December 31. The company must record five months of depreciation expense on December 31 (August‐December).

Under the straight‐line method, the first full year's annual depreciation expense of $16,000 is multiplied by five‐twelfths to calculate depreciation expense for the truck's first five months of use. $16,000 of depreciation expense is assigned to the truck in each of the next four years, and seven months of depreciation expense is assigned to the truck in the following year.

|

Straight-Line Depreciation

|

|

|

Depreciable Cost

|

|

|

|

|

Cost

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$90,000

|

|

Year 1 (5 mo.)

|

5/12 × 20%

|

×

|

$80,000

|

=

|

$ 6,667

|

$ 6,667

|

83,333

|

|

Year 2

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

22,667

|

67,333

|

|

Year 3

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

38,667

|

51,333

|

|

Year 4

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

54,667

|

35,333

|

|

Year 5

|

20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

16,000

|

70,667

|

19,333

|

|

Year 6 (7 mo.)

|

7/12 × 20%

|

×

|

80,000

|

=

|

9,333

|

80,000

|

10,000

|

Under the declining‐balance method, the first full year's annual depreciation expense of $36,000 is multiplied by five‐twelfths to calculate depreciation expense for the truck's first five months of use. In subsequent years, the truck's net book value is higher than it would have been if a full year's depreciation expense had been assigned during the first year, but the declining‐balance method's calculation of depreciation expense is otherwise unchanged.

|

Double-Declining-Balance Depreciation

|

|

|

Beginning-of-Year Book Value

|

|

|

|

|

Year 1 (5 mo.)

|

5/12 × 40%

|

×

|

$90,000

|

=

|

$15,000

|

$15,000

|

$75,000

|

|

Year 2

|

40%

|

×

|

75,000

|

=

|

30,000

|

45,000

|

45,000

|

|

Year 3

|

40%

|

×

|

45,000

|

=

|

18,000

|

63,000

|

27,000

|

|

Year 4

|

40%

|

×

|

27,000

|

=

|

10,800

|

73,800

|

16,200

|

|

Year 5

|

40%

|

×

|

16,200

|

=

|

6,200 *

|

80,000

|

10,000

|

|

Year 6 (7 mo.)

|

|

|

|

|

0

|

80,000

|

10,000

|

Limited to $6,200 so book value does not go below salvage value.

Under the sum‐of‐the‐years'‐digits method, the first full year's annual depreciation expense of $26,667 is multiplied by five‐twelfths to calculate depreciation expense for the truck's first five months of use. During the second year, depreciation expense is calculated in two steps. The remaining seven‐twelfths of the first full year's annual depreciation expense of $26,667 is added to five‐twelfths of the second full year's annual depreciation expense of $21,333. This two‐step calculation continues until the truck's final year of use, at which time depreciation expense is calculated by multiplying the last full year's annual depreciation expense of $5,333 by seven‐twelfths.

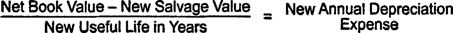

Revising depreciation estimates. Depreciation expense calculations depend upon estimates of an asset's useful life and expected salvage value. As time passes, a number of factors may cause these estimates to change. For example, after recording three years of depreciation expense on the truck, suppose the company decides the truck should be useful until it is seven rather than five years old and that its salvage value will be $14,000 instead of $10,000. Prior financial statements are not changed when useful life or salvage value estimates change, but subsequent depreciation expense calculations must be based upon the new estimates of the truck's useful life and depreciable cost.

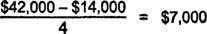

Under the straight‐line method, depreciation expense for years four through seven is calculated according to the following equation.

Revising Straight‐Line Deprciation

Assume that the company purchased the truck at the beginning of an annual accounting period. The previous table shows how depreciation expense was calculated during the truck's first three years of use. The truck's net book value of $42,000 at the end of year three is reduced by the new, $14,000 estimate of salvage value to produce a revised depreciable cost of $28,000. The revised depreciable cost is divided by the four years now estimated to remain in the truck's useful life, yielding annual depreciation expense of $7,000.

Similar revisions are made for each of the other depreciation methods. The asset's net book value when the revision is made along with new estimates of salvage value and useful life—measured in years or units—are used to calculate depreciation expense in subsequent years.

Depreciation for income tax purposes. In the United States, companies frequently use one depreciation method for financial reporting purposes and a different method for income tax purposes. Tax laws are complex and tend to change, at least slightly, from year to year. Therefore, this book does not attempt to explain specific income tax depreciation methods, but it is important to understand why most companies choose different income tax and financial reporting depreciation methods.

For financial reporting purposes, companies often select a depreciation method that apportions an asset's depreciable cost to expense in accordance with the matching principle. For income tax purposes, companies usually select a depreciation method that reduces or postpones taxable income and, therefore, tax payments. In the United States, straight‐line depreciation is the method companies most frequently use for financial reporting purposes, and a special type of accelerated depreciation designed for income tax returns is the method they most frequently use for income tax purposes.